From his earliest memories, Mike Norton recalls playing with model ships and submarines with his older brother. His older brother had a ship, and he had the sub. The small pond on the Circle H ranch where he spent his early life before Lake Granby filled up gave little boys' imaginations an ocean. Marbles gave them depth charges. "But I could never find a way to shoot marbles from the sub," Norton laughingly remembers. As the water literally rose above his home, it shaped his life.

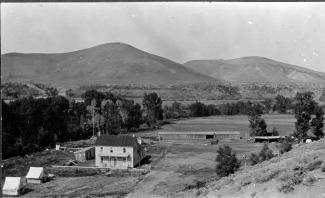

The history of Lake Granby and the Norton Marina goes as deep as the water, literally. Grand County's pioneer ranching history lurks at the lake's bottom, sharing its place with rainbow trout amid the vast water supply for eastern Colorado and beyond. Before the lake filled up as part of the Colorado Big Thompson project, ranches like the Lehmans, Knights and Harveys had been stage stops, cattle and dude ranches and even an airstrip used by Charles Lindbergh.

Mike's dad Frank came to Grand County to ranch. "All I ever really wanted to do first was to be a rancher here," Frank Norton told the Sky-Hi News back in 1997. At fifteen or sixteen years old, Frank Norton in a Model T Roadster traveled from Okmulgee, Oklahoma to Grand County, where he "fell in love" with the ranch that his mother and step-father started around 1930. The Circle H, started by his step-father Jim Harvey in the valley that is now Lake Granby, became his summer home.

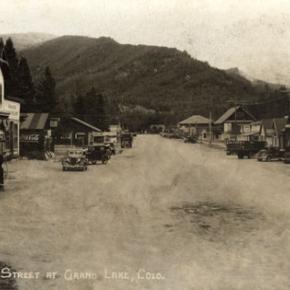

By all accounts, Frank Norton loved ranching. The Circle H "was a working ranch and a dude ranch." Harvey's ranch provided a spectacular backdrop highlighted by the Indian Peaks, reaching 13,000 ft high along the Continental Divide. The Circle H offered a caricature map for tourists looking for a real western experience. It led them over Berthoud Pass along hwy 40 to hwy 34 and then right at the Circle H sign to the Ranch. Leaving on horses from the Circle H, Frank Norton and Jim Harvey took them into a vast and remarkable country that, for the most part, can only be reached on foot today.

In those days, the area now protected as the Indian Peaks Wilderness Area faced less threats from overuse. Ranchers hunted the region to supplement the sometimes skinny winter rations. "Jim Harvey shot two elk from his saddle," Mike Norton proudly recalls of his grandfather as we look at a romantic image of Harvey on horseback. Nowadays, quotas limit use through the peak season. The National Park and Forest Service restrict horse traffic and campfires as well. Early Harvey and Norton history highlight a different time and place, when the remote reaches of Indian Peaks could still be reached by trusting a cowboy with a Winchester rifle to get you there and back safely.

For Mike Norton, the water that drowned out his family's ranching history also floated Norton Marina. Going from ranching to the marina business may seem an odd transition, but Mike's family history shows how flexible they were! Frank Norton spent his early youth traveling with his father's tent show, Norton's comedians. "Dad had such funny stories about that," Mike says. When the traveling troupe era ended (talkies and the Great Depression meant "they didn't eat too well sometimes"), Frank Norton moved to Oklahoma with his father before finally joining his mother and Jim Harvey in Grand County.

Regardless of his occupation, Frank Norton was a showman. Remarkable old photos save the rich history of pack trips into the Indian Peaks area, camp sites on the shores Lake Monarch and rich harvests of rainbow trout. But Frank Norton and his horse Oak rearing high like the lone ranger really show Frank Norton's flare and charisma.

In many ways, Norton Marina continued the Circle H's heritage. Frank's marina included the Gangplank, a restaurant and dancehall that looked like a boat, with porthole windows and originally a rainbow trout aquarium for the bar. His admiral's hat, which Mike still has today, replaced his cowboy hat and a 25 foot Chris Craft named the Bonnie B replaced old Oak as his ride. More or less, this is the world in which Mike Norton grew up.

Growing up Frank's son meant work too. "I was 8 or 10 years old" when we started "Norton's Ark," Mike smiles, referring to the Gangplank restaurant. It was the early fifties in Grand County. "What backhoe?"

No bailouts either! "Those first few years, I nearly starved to death," Frank Norton once told a reporter. "But," he added, "every year the business kept growing and before I knew it we had a good marina going." Before it was over, Norton Marina fulfilled Frank's dream of a family business, only in "boating recreation" instead of ranching!

"It wasn't all roses," Mike agrees. As a boy, Frank Norton went to military school. "They disciplined him and he used the same technique on his kids." Frank expected his kids to help and to obey his commands, without question. Using Tide and a G.I. scrub brush, Mike Norton recalls scrubbing lower units. They painted wooden boats in the wintertime in the shop. The kids came in from school, changed clothes and started working. "Dad and mom had a lot of kids cause they needed a crew!"

Maybe his most memorable job was cleaning out the septic tanks for the cabins that his dad built to help offset the lack of income at a Rocky Mountain marina during winter. After digging up the lids, "dad would put a ladder into the septic tanks." Then, Mike crawled in and shoveled out the waste while his dad hoisted the buckets out. "I was so glad when Ernie Seipps started his septic clean out business," Mike says as we motor along beside Grand Elk Marina's covered docks on a pontoon boat.

The hard work and experience at the marina paid off when Mike joined the military. Like so many of his generation, Mike received his notice to join ground forces in Vietnam. Luckily, about that time, Navy recruiters were in Granby. They showed a strong interest in a National Honors Society student who lived a life on water! The pieces of the puzzle fit, and "that got me in the Navy," says Mike with real appreciation.

In 1973, the family tradition passed on to Mike and his brother Frank when they bought the marina business from their dad. A lifetime of experience came with them. But it took more than dock maintenance, boat service and customer service to run Norton Marina. And, as the brothers took over, the old Admiral Frank Norton stayed in the house he had built next door to the gangplank, insuring that his strong personality was never far away.

Lots of obstacles exist for a marina on public lands. As Mike took over sole ownership from his brother, he also fought to bring the marina under the National Forest Service instead of the National Park Service, which effectively removed the "power of condemnation." "We had to fight for our livelihood," Mike explained when he sold the Marina in January of 1997.

Mother Nature challenged the marina too. Ice might remain on the water for half of May. June snowstorms blow in monster clouds, as awe-inspiring as the calm sunsets. Freezing rain rips into all but the best prepared boaters nearly any time of year, and hailstorms can hit in a heartbeat. "We're like farmers in that way," Mike recalled. "Drought, winters, high water, low water, you can't really help, we understand that."

On the other hand, the glassy waters of Lake Granby reflect the awe-inspiring Indian Peaks along the Continental Divide on calm, sunny days. Tourists and locals try their luck catching the Mackinaw that makes it attractive to sportsmen and women. Intrepid wake boarders mix with sweet sailboats against a beautiful background of rugged peaks that reach high above tree line. On those days, it's hard to think of a more spectacular place.

Through it all, Mike Norton clearly enjoyed his life at Norton Marina. "I liked being out in the elements with the boating public." He also counts the independence of self-employment and the uniqueness of the marina as blessings in his "good life."

Grand Elk runs the marina today (2009). Its operation rents out slips and moorings, daily pontoon boats and other related services. It's as beautiful as ever to peer across the lake at sunrise in August, and it's as cold and forbidding as ever when the winter winds whip across the thick ice an snow of the lake in January. Few wooden hulls appear during summer season as in the old days, but beautiful boats, both motor and sail, still surround the Marina.

Yes, its original character remains, not far from the surface. The Gangplank changed its name to Mackinaws, where customers in the main room still look out portholes across the lake to the rugged outline of Indian Peaks Wilderness Area, although there is no longer as much space on the dance floor. Those familiar with Indian Peaks recognize old Abe Lincoln lying in his grave along the Continental divide, where Mike's early ranching family led pack trips and today can still be reached, albeit under more controlled circumstances. Today's anchored concrete docks and gas dock continue the process that started with Frank Norton using finger docks that Mike staked in the ground and an old chicken coup from the Circle H to fuel boats.

And in all of Grand Elk Marina's features and history, Frank Norton and his family exist. In the house that they built on site where all of his children were photographed as they grew up and as they graduated from Middle Park High School. In the restaurant where Mike remembers finding the nerve to ask pretty young gals to dance. And, in the numerous family photos that show a smiling, handsome Frank Norton and his attractive family surrounded by high mountains, wooden Chris Craft and a sense of high expectations.

Mike remembers his dad as the "greatest storyteller I've ever known," which he used to his advantage in all occupations. In 2001, I met Frank Norton, only once before he died the next year. He told us about the time Jim Harvey knocked the federal agent who came to tell take their land away to the floor, placed a foot on his chest and said, "If you get up, I'll knock you down again." We could see it happening as he told the story more than 50 years later.

But the story continues beyond Frank Norton. From traveling tents shows to dude ranches to a forty-plus year family run marina, the Nortons made one of Grand County's most enduring "institutions." Entertaining, industrious, and life-loving, Mike simply says, "It's been a really good life." And that's a family tradition.